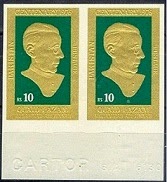

75Th Death Anniversary of Allama Muhammad Iqbal

Commemorative Postage Stamp April 21, 2013:- Allama Sir Muhammad Iqbal was

a poet, philosopher, lawyer and politician born in Sialkot on 9th

November 1877. His poetry in urdu, Arabic and Persian is considered to be among

the greatest of the modern era and his vision of an independent state for the

Muslims of British India was to inspire the creation of Pakistan. He is

commonly referred to as Allama Iqbaly. One of the most prominent leaders of the

All India Muslim League, Iqbal encouraged the creation of a “state in northwestern

India for Indian Muslims” in his 1930 presidential address. Iqbal encouraged

and worked closely with Muhammad Ali Jinnah and he is known as

Muffakir-e-Pakistan (“The Thinker of Pakistan”), Shair-e-Mashriq (“The Poet of

the East”), and Hakeem-ul-Ummat (“The Sage of Ummah”). He is officially

recognized as the “national poet” in Pakistan.

Iqbal was educated initially by

tutors in languages and writing, history, poetry and religion. His potential as

a poet and writer was recognized by one of this tutors, Syed Mir Hassan, and

Iqbal would continue to study under him at the Scotch Mission College in

Sialkot. He studied at Murray College Sialkot.

Iqbal entered the Government

College Lahore where he studied philosophy, English literature and Arabic and

obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree. He won the gold medal for topping his

examination in Philosophy. While studying in his Masters’ Degree Progrem, Iqbal

came under the Wing of Sir Thomas Arnold, a scholar of Islam and modern

philosophy at the college. Arnold exposed the young man to the Western culture

and ideas, and served as a bridge for Iqbal between the ideas of East and West.

Iqbal was appointed to a readership in Arabic at the Oriental College, Lahore.

He published his first book in Urdu “The Knowledge of Econimocs” in 1903 and

the patriotic song, Tarana-e-Hind (Song of India) in 1905.

He obtained a Bachelor of Arts

Degree from Trinity College at Cambridge in 1907, while simultanewusly studying

law at Lincoln’s Inn, from where he qualified as a barrister at Law in 1908.

Togetherr with two other politicians, Syed Hassan Bilgrami and Syed Ameer Ali,

Iqbal sat on the subcommittee which drafted the Constitution of the Muslim

League. In 1907, Iqbal traveled to Germany to pursue his Doctorate from the

Faculty of Philosophy of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat at Munich. Working

under the supervision of Friedrich Hommel, Iqbal published a thesis titled:

“The Development of Metaphysics in Persia”.

Upon his return to India in 1908,

Iqbal took up Assistant Professorship at the Government College Lahore, but for

financial reasons he relinquished it within a year to practice law. Iqbal’s

poetic works are written mostly in Persian.

Among his 12,000 verses of poems,

about 7,000 verses are in Persian. In 1915, he published his first collection

of poetry, the Asrar-e-Khudi (Secrets of

the Self) in Persian.

Iqbal’s 1924 publication, the Payam-e-Mashriq (The Message of the East)

is closely connected to the West-Ostlicher Diwan by the famous German poet

Goethe. In his first visit to Afghanistan, he presented his book

“Payam-e-Mashreq” to King Amanullah Khan in which he admired the liberal

movements of Afghanistan against the British Empire.

The Zabur-e-Ajam (Persian Psalms), published in 1927, includes the

poems Gulshan-e-Raz-e-Jadeed (Garden of New Sectets) and Bandagi Nama (Book of

Slavery).

Iqabal’s 1932 work, the Javed Nama is named after and in a

manner addressed to his son, who is featured in the poems, and follows the

examples of the works of Ibn Arabi and Dante’s “The Divine Comedy”, through

mystical and exaggerated depiction across time.

Iqbal’s first work published in

Urdu, the Bang-e-Dara in 1924, was a

collection of poetry written by him in three distinct phases of his life.

Published in 1935, the Bal-e-Jibril

is considered by many critics as the finest of Iqbal’s Urdu Poetry, and was

inspired by his visit to Spain, where he visited the monuments and legacy of

the kingdom of the Moors. It consists of ghazals, poems,quatrains, epigrams and

carries a strong sense of religious passion.

Iqbal’s final work was the Armughan-e-Hijaz published posthumously

in 1938. The first part contains quatrains in Persian, and the second part

contains some poems and epigrams in Urdu.

Iqbal’s second book in English,

the Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, is a collection of his six

lectures which he delivered at Madras, Hyderabad and Aligarh; first published

as a collection in Lahore, in 1930. Sir Muhammad Iqbal was elected President of

the Muslim League in 1930 at its session in Allahabad, in the United Provinces

(UP) as well as for the session in Lahore in 1932. In his presidential address

on December 29, 1930, Iqbal outlined a vision of an independent state for

Muslim-majority provinces in northwestern India.

He thus became the first

politician to articulate that Muslims are a distinct nation and thus deserve

political independence from other regions and communities of India.

Iqbal was of the view that only

Muhammad Ali Jinnah was a political leader, capable of preserving Muslim unity

and fulfilling the League’s objectives on Muslim political empowerment. Iqbal

was an influential force on convincing Jinnah to end his self-imposed exile in

London, return to India and take charge of the League with a new agenda – the

establishment of Pakistan.

Speaking about the political

future of Muslims in India, Iqbal said: “There is only one way out. Muslims

should strengthen Jinnah’s hands. They should join the Muslim League. Indian

question, as is now being solved, can be countered by our united front against

both the Hindus and the English”.

Iqbal is commemorated widely in

Pakistan, where he is regarded as the ideological founder of the state. His

birthday November, 9 is annually commemorated in Pakistan as Iqbal Day and is a

national holiday.

In 1933, after returning from a

trip to Spain and Afghanistan, Iqbal’s health deteriorated. He spent his final

years working to establish the Idara Dar-ul-Islam. Iqbal ceased practicing law

in 1934 and he was granted pension by the Nawab of Bhopal. After suffering for

months from a series of protracted illnesses, Iqbal died in Lahore on 21st

April 1938. His tomb is located in the space between the entrance of the

Badshahi Mosque and the Lahore Fort, Lahore.

To commemorate 75th

Death Anniversary of Allama Muhammad Iqbal Pakistan Post is issuing a

commemorative postage stamp of Rs. 15/- denomination on April 21, 2013.